This guest blog series showcases blog posts from participants who took part in the international symposium ‘Ecologies of Labour’ on 15-16 June that we co-organised with colleagues from Nottingham Trent University’s Centre for Policy, Citizenship and Society, the JK Lakshmipat University Centre for Communication &

Critical Thinking, and the Tata Institute of Social Sciences.

Lost connections? An exploration of the estrangement of young fishers in South India from their indigenous knowledge systems amidst climate change

Devendraraj Madhanagopal

Assistant Professor I – School of Sustainability, XIM University (Odisha, India)

Email: devendraraj.mm@gmail.com

For generations and centuries, marine fishing in the coastal regions of southern India has been deeply intertwined with caste, an influential social institution in India. The fishing communities inhabiting these coastal spaces have, over time, cultivated a rich tapestry of cultural and social norms, indigenous governance systems, and local ecological knowledge systems that are uniquely adapted to their marine environment, fishing practices, and coastal spaces. These indigenous knowledge systems of marine fishing communities are the result of centuries of accumulated experience and expertise and represent a nuanced and rich understanding of the marine ecosystem that has been passed down from generation to generation.

As Berkes (1993) rightly pointed out, there is no such universally accepted definition for the term “traditional ecological knowledge.” To define this, we have to divide this term into two “traditional” and “ecological knowledge.” In conventional understanding, “traditional” defines that the knowledge that is continued to transfer from ancestors in the form of social beliefs, principles, behaviours, and practices. This understanding of “traditional” in knowledge systems is problematic as the society changes over time and so their practices and knowledge systems, making difficult to categorize as “traditional.” As Berkes (1993) continued to bring forward further conceptual challenges in defining “ecological knowledge” he noted that the term “ecology” is mostly narrowly understood as a branch of biology through the lens of western science.

Many native communities of the Canadian North refer their knowledge as “knowledge of the land” rather than “ecological knowledge.” Moreover, in a strictest sense, native peoples/indigenous communities are not scientists. Hence, the terminology of “ecological knowledge” is also problematic. In order to avoid any conceptual misunderstanding and conflicts, the paper on which this blog piece is based consistently adopts the term “indigenous knowledge” to encompass two key concepts: “traditional ecological knowledge” and the “local and indigenous knowledge” systems of Pattinavar fishers. By adopting the term “indigenous knowledge,” this piece seeks to encompass the shared ancient wisdom, understanding, and traditional ecological and fishing practices that have been passed down through generations within the cultural and ecological context of the Pattinavar community in India. These indigenous knowledge systems of Pattinavars are deeply embedded in the coastal and environmental spaces that form the backdrop of their lives, marine fishing livelihoods, and traditions.

The Pattinavar community has historically thrived along the Coromandel coast of Tamil Nadu and Puducherry. Tamil Nadu, a prominent coastal state on the east coast of India, boasts second largest coastline spanning approximately 1076 kilometres next to Gujarat state in India. Within Tamil Nadu, the Coromandel Coast encompasses seven districts, covering around 357 kilometres of coastline from Pulicat to Point Calimere. Furthermore, marine fishing serves as a significant livelihood for hundreds of thousands of small-scale fishers of this coast. It is deeply rooted in the ancestral occupation of around a million fisher-people across Tamil Nadu. The Coromandel coast of Tamil Nadu has a longstanding and illustrious history of marine fishing, dating back to the Sangam age, a period roughly spanning from 300 BCE until 300 CE. (Madhanagopal, 2023). Extensive research provides compelling evidence of the high vulnerability of this coast to climate change and coastal disasters. This region suffered a catastrophic event in 2004 when the Indian Ocean Tsunami struck, resulting in the tragic loss of thousands of lives, and causing long-term impacts on infrastructure, marine fisheries, and coastal biodiversity. This catastrophic event not only caused profound disruptions to their lives and economic stability but also had far-reaching consequences for their indigenous knowledge systems, including their understanding of the local marine environments, coastal spaces, and fishing practices.

In recent decades, Pattinavar fishers have experienced significant transformations in their ways of life and means of subsistence. These changes have been largely driven by the interplay between capital-intensive fishing methods and the intensification of climate risk events and other environmental stressors. The primary data and major discussions of this paper revolves around the Nagapattinam district, situated in the south-eastern coastal region of Tamil Nadu, which also forms a part of the Coromandel Coast. Provided this background, this paper, through rigorous fieldwork and the resulting selected qualitative insights, shows that the young Pattinavar fishers are losing their connection with their local ecological (indigenous) knowledge systems by and large in the recent decades. Losing connections does not just stop with their indigenous knowledge systems but extends beyond the realm of traditional livelihood practices amidst the impacts of climate change. In this context, this paper interrogates the multiple questions behind losing the touch of indigenous knowledge systems and discusses the future trajectory of these knowledge systems amidst multiple environmental stressors and climate change.

Select references:

Berkes, F. (1993). Traditional ecological knowledge in perspective. In J.T. Inglis (Ed.), Traditional Ecological Knowledge, Concepts and Cases (pp. 1-9). Ottawa: Canadian Museum of Nature/International Development Research Centre.

Madhanagopal, D. (2023). Local Adaptation to Climate Change in South India: Challenges and the Future in the Tsunami-Hit Coastal Regions. Abingdon & New York: Routledge.

Devendraraj Madhanagopal (Ph.D.) is an Assistant Professor (I) in the School of Sustainability at XIM University (Odisha, India). He holds a Ph.D. in Sociology from the Department of Humanities and Social Sciences, Indian Institute of Technology Bombay (Mumbai, India). He is the recipient of several international travel grants/fellowships. His works appear in Environment, Development and Sustainability & Metropolitics journals. He is the author of “Local Adaptation to Climate Change in South India Challenges and the Future in the Tsunami-hit Coastal Regions” (2023; Routledge, UK). He is the leading and corresponding editor of the following edited book volumes: i. Environment, Climate, and Social Justice: Perspectives and Practices from the Global South (2022; Springer Nature Singapore). ii. Social Work and Climate Justice: International Perspectives (2023; Routledge, UK) iii. Climate Change and Risk in South and Southeast Asia: Sociopolitical Perspectives (2022. Routledge, UK).

Ecological Labour in Adivasi Knowledge and Practices: The Case of Jungle Mahals, Eastern India

Dr Nirmal Kumar Mahato

The ecological labour prevalent in traditional knowledge and practices is shared among the Adivasis/tribes of Jungle Mahals, and will provide insight into a model of labour which cares for both humans and non-humans. The labour-Adivasi relationship has been least discussed, and thus further research is required on its political, economic, and historical dynamics. As a result of immense environmental and climatic changes which disrupt human welfare and biodiversity loss, new forms of resilience have developed for adaptation. In the colonial and post-colonial periods, Adivasi people were deprived of their traditional rights over using natural resources. In the newly emergent landscapes, they felt alienated, with the survival of the community depending on the healthy ecology surrounding them. It can be achieved through the ‘moral economy’ of the Adivasis, based on the ideas of mutual dependence between humans and non-humans. In their worldview, they describe themselves as custodians of- and also express care for- non-human others.

The Adivasi worldview (Jansim binti and Karam binti) advocates a mutual dependence between the human and non-human world. According to the Adivasi, humans are not considered above other animals or plants, as these provide for the habitation of human beings. Thus, the Adivasi worldview is contrary to the European worldview, wherein the human is placed above other animals. Rather, their traditional views of ecosystems see humans as arguably integrated with their surrounding environment. With their limited and sustainable utilization of natural resources, the Adivasi practice their ecological moral economy, which was a part of their community labour, to sustain their life and livelihood. As their notion of time is cyclic, there is the unending repetition of cycles within cycles. Moreover, as there is no anxiety about the future, they enjoy a great amount of sleep and leisure. The subject matter of their oral tradition was a symbiotic relationship between Adivasis and nature, as well as a denial of self-conscious and self-centered behaviors. There was no effort to score a victory over nature. Their oral tradition revealed two parallel experiences; the public or the collective experiences, and personal feelings and expressions. There was less individual devotion in this moral discourse. With very small cases of specialization, each individual is proficient in all aspects of life.

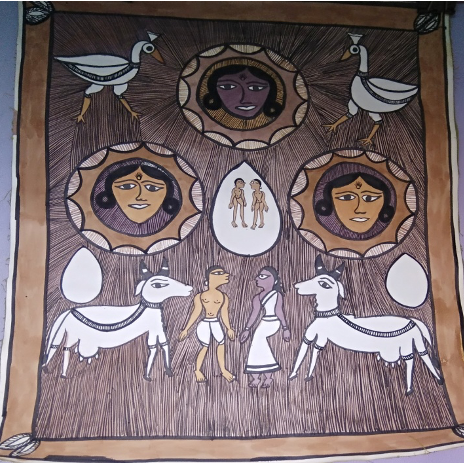

Picture1 : Scroll painting of the Santals Adivasis, which describes the creation myth

The Mudis are a group of Oraon (‘earth worker’/ ‘tank digger’), and have expertise in hydro-technical knowledge, including pond making. Their approach is to sustainably transform nature, with new water bodies becoming a new source in which people create an ecosystem, and essentially, this becomes a social entity. The Adivasis traditionally learnt different kinds of ecological engineering and landscape management, and created ponds in such a way that they did not damage the wider landscape. Adivasi ways of rainwater harvesting accelerated landscape heterogeneity as they planted trees on the banks of the pond, and created an environment to develop and sustain wider ecosystems. Such newly transformed landscapes by the Adivasis were the outcome of their community-based labour system. Here the Mudis were invited to construct a pond and gained respect in society.

While discussing the environmental history of Southeast Asia rubber, Ulbe Bosma argues that landscapes are not only regarded as natural entities, but are also the outcome of labour systems.[1]

Picture: Tank digger/ Earth worker ( Mudi/Kora)

The close relationship between labour and nature is revealed when Adivasi healers collect gums without damaging or tapping the trees for preparation of indigenous medicine, or exchange with other communities. During the season of harvest, they prefer to collect the exposed roots of plants near the water channel for the preparation of indigenous drugs so that they deal with the plant with care. Women hold important knowledge about medicinal floras, and also help in biodiversity conservation, as they know the methods of seed conservation. Women and girls have special skills and knowledge in collecting mushrooms, tubers, and leaves because they have an intimate knowledge of what is edible, along with the correct location and timing of collection. Adivasi society emphasizes unalienated labour, reciprocity, and community work. Through their landscape management, the Adivasis help prevent ecological damage, and ensure productivity with ecological labour.

[1] Bosma, Ulbe. 2019. Making of a Periphery: How Island Southeast Asia Became a Mass Exporter of Labor, New York, Columbia University Press, p.7.

Locating labor in climate-induced crisis: The re-emergence of indigenous practices and tactics

Nivash Prakash – Ph.d student at the Centre for Political studies, Jawaharlal Nehru University

The recent years have been troublesome for humankind, with crisis upon crisis unfolding. We all know how the covid-19 has had tremendous consequences for people all over the world. In addition to this, the climate onslaught is another worrisome issue which has become a major issue, particularly in the global south. In South Asia, heatwaves are becoming frequent but under-explored events which have disastrous consequences on humankind, especially the most marginalised of society, any crisis primarily impacts the most disadvantaged and vulnerable segments of a population. Therefore, the central aim of this paper is to assess the impacts of excessive heatwaves on the daily wages of labourers vis-a-vis the changing the nature-human relationship in the wake of the latest climate crises, which especially impact the labouring class. The paper will trace how the phenomenon of heatwaves, which have become frequent in megacities like Delhi, affect labour productivity.

The impact of this recent climate-induced seasonal crisis is becoming apparent among the labouring class. The continuous rise of temperatures every year and the presence of a crowded population involving multiple industries, high energy use and pollution caused by carbon emissions make the lives of the poorest acutely distressing. Existing research on these emerging climate changes suggests that the difficult experiences during the summers further marginalise lower-class populations. Such works observe at a primary level that heat waves create more vulnerabilities and increase the level of exploitation and distress among daily wage earners living in slums in various ways, such as by restricting work opportunities, thus sometimes forcing them to return home. Moreover, their daily civic amenities suffer, especially when compounded by other stressors such as water scarcity and severe health issues. These often add extra expenses to their limited income, causing a decline in productivity and physical suffering. Looking at these difficulties and the range of issues impacting everyday life, this work wants to address the urgent crisis of climate change by examining the phenomenon of heatwaves and their impacts on the labouring class.

Based on empirical data collected between June and July in 2022 and 2023, the paper examines in what ways the heatwave has crippled labour. What informal jobs are halted during heatwaves, and how does this impact casual labour? What are the strategies and tactics adopted by labourers in order to overcome these difficulties? Do these strategies also inhibit the culture-specific practices they used earlier as indigenous groups? How are heatwaves impacting their domesticated animals? What is the role of state and local government in enhancing resilience against climate-induced crises? The above questions will be addressed through an extensive empirical study spanning three informal settlements in Delhi. My methodology primarily includes primary data collected through In-depth interviews, focus group discussions with daily wage labourers engaged in a diverse range of informal occupations and immersive participant observation at their workplace and residential areas. I also aimed to document their daily routines and activities in the midst and wake of extreme heat events. Moreover, the paper explores the ways in which the nature-human relationship is being reshaped amidst these climate crises.

Nivash Prakash is currently a Second year Ph.d student at the centre for Political studies of Jawaharlal Nehru University working under the supervision of Dr. Rajarshi Das Gupta . The focus area of his research is the ongoing Migrant Labor crisis and daily wage earners working in the informal sector especially in the capital city of Delhi. Nivas looks forward to understanding and working on the emerging contemporary questions related to migrant labor and urban poor population, especially in the light of the withdrawal of state support in these areas.

Is sustainable ecological? ‘World-Class’ city making and ecological constraints

Divya Priyadarshini

The predominance of cities in the contemporary era has resulted in the emergence of a group of ‘global cities’, which have claimed strategic positions in the world economy. These cities influence and govern the imaginations of others, as plans and maps are designed, with developed cities often imagined as the ideal model for development in the global south. In addition to making the cities economically viable and self-reliant, ‘world class’ cities now also need to be sustainable. New projects and city plans are now developed as a reconciliation of environmental, social and economic needs. However, in most instances it is observed that the geography, physicality, ecology, social and other cultural aspects of the redesign and re-imagination of cities are ignored. Specifically, the extent to which the new evolving ‘world-class cities’ are ecological can be debated. The present view draws from the continuous re-configuring of Delhi and the diverse ways in which the city has been imagined. Neoliberal outcomes can be diverse, contested and negotiated and yet the main trend has pushed the city of Delhi in the somewhat predictable direction that seeks to attain the image of a ‘world-class-city’.

Historically, Delhi has been governed by Master Plans for ten-year periods with other events which have led to the tweaking of these plans. Delhi hosted the Asian games twice in the past, and then the commonwealth games in 2010 in an effort to uplift the image of the city as a ‘world-class city’. In order to expand government housing and create commercial infrastructure in the national capital, the government approved the redevelopment of seven centrally located residential colonies in Delhi in 2016. Since the 1970s, many evictions and relocation drives have changed the geography of Delhi and its residents. The land plans have been changed and trees have been uprooted. The Yamuna ecosystem has been destroyed ‘but for the city’s managers and planners, the river has become the new frontier in the city’s transformation’ (Follmann 2016).

Asher D Ghetner (2011) has very well demonstrated how city planning is often governed by aesthetic norms and visual order. Baviskar (2003) used the term ‘bourgeois environmentalism’ to explain how climate change, environmentalism and sustainability in the Delhi metropolitan area are designed and structured around the privileged citizens’ notions and ideas of nature. The emphasis of urban development to build sustainable ‘world-class’ cities has not only led to structural but also ecological re-designing. The labour involved in designing and planning centres around a handful of planners and privileged individuals. This has been labeled as sustainable and interchangeably used as ecological.

The redevelopment projects that keep occurring in Delhi have changed its landscape, and also disturbed the ecological balance that had existed for many years. Small housing complexes are being replaced by large multi-storey complexes, thus not only putting a pressure on the infrastructure but also on access to other basic necessities like water, power and sewage systems. Trees have been removed to make way for visually appealing palm trees. More paved paths, concrete parks and landmarks have replaced the otherwise natural ones in service of an aesthetic imagination of planning Delhi. However, in the effort to make Delhi ‘world-class’, all the attempts and planning have been labeled as sustainable, or ‘ecologically balanced’. Substantial efforts and labor have gone into getting the environmental clearances for all the projects in Delhi. On paper, the (re)designing of the city spaces makes for a planned, aesthetic, sustainable city, but in reality it has become an increasingly less favourable city to live in.

Divya Priyadarshini has a PhD from the Department of Sociology, DSE, University of Delhi. Her dissertation focussed on resettlement projects in Delhi and how the everyday of such resettlement colonies are since its inception. She has been exploring and researching the discourses of urban development in Delhi since 2012. She has a keen interest to understand what actually makes a city. Having worked for policy think tanks and as guest lecturer in different universities in Delhi, presently she is an independent researcher.

Precarity, Labour and Landscape: Seasonal salt harvesters of Gujarat in the Little Rann of Kutch, Gujarat, India

Bhavna Harchandani – Doctoral Candidate at Humanities and Social Sciences, Indian Institute of Technology Gandhinagar, Gujarat, India

Seasonal migration for labour is understood as an outcome of poverty and lack of employment opportunities that force villagers to migrate for six months or more to survive. But for the traditional salt harvesters (Agariyas) of the Little Rann of Kutch (LRK) in Gujarat, migration for labor is understood beyond the lens of economic subsistence. The ancestral connection with LRK for traditional occupation of salt harvesting drives the resilient Agariyas to endure the harsh and vulnerable environmental conditions and exploitative labor markets, inside and outside of LRK. The seasonal dynamism of LRK, which changes every quarter, affects the lifeworld of the traditional Agariyas, who are responsible for the 30% of the total salt production of India’s leading state of salt export, Gujarat. However, the production of salt using sub-soil brine is termed as ‘exploitative’ extraction and mining by environmentalists, and the harvesters are depicted as ‘dangerous’ for the survival of the local equine ‘Gudkhar’ by the forest officials. The implementation of Wildlife Act 1972 and the Forest Rights Act 2006 has ignored the presence of Agariyas in LRK, deprived them of their rights and made their presence vulnerable in the region.

Based on Ingold’s method of studying the people through temporality of the landscape, the paper explores the labor of harvesting salt ritualized as a form of precarious living in the arid form of Rann. The affect of labor in the Rann is embodied in the lifeworld of Agariyas through their lived experiences. Drawing from the data collected through eight months of rigorous ethnographic research in the Rann (September 2021 to April 2022), examining the embodiment of ‘Being Agariyas in LRK’, I argue that the labor of salt harvesters should not be understood in isolation for the production of salt only. The events of migrating and establishing their dwelling in desert of Rann together constitute their labor. For these events bring the Rann into a state of ‘Being’. The Agariyas interpret their ‘returning to the Rann’ as a customary ritual to maintain an ecological balance of natural resources, thereby transcending their labor practices as practice of ‘Care’ and ‘Protection’ of the biodiversity and landscape which sustain their traditional occupation.

The integrated nature of the landscape is depicted as an extension of the harvester, as a part of ‘Nature’ that invokes the emotions of protector of the biodiversity in the desert and rightful presence in the desert against the institutional appropriation of their presence that threatens the biodiversity and advocates their eviction. They contend that their presence in the landscape is integral in identifying the landscape as Rann for the marshland that is reckoned as a wasteland, and is reincarnated as useful and fertile, which otherwise is speculated to be barren. Their manual labor is responsible for the yearly replenishing of the underground brine and solar-dependent sustainable harvesting, and their dwellings turn the Rann into a living world which benefits the passersby and tourists as they serve as pathfinders and rescuers for those otherwise ‘lost’ in the roadless Rann. Their unrecognized form of labor for salt is masked by the ambiguous State recognition that portrays them as destitute and lacking basic necessities such as health, education and adequate protection of salt during natural disasters.

The seasonal change of landscape from wetland to marshland and dryland is personified in the lives of salt harvesters who have embodied the Rann in their everyday lives. The everyday choice of salt harvesters is based on their lifeworld in the desert which remains the same even after they touch their base in the village. The body of the salt harvester, when outside the Rann for ‘labor’ during the off season, is considered a ‘threat’ as it competes with regular daily wage laborers through skills, whereas the latter is embraced and praised for enduring the precarious environment. Thus, the Agariyas prefer to work in allied works of the salt industry instead of venturing into other forms of daily wage labour. The salt harvesters’ precarious labor in the Rann is the record of their past generations and endurance that they continue to dwelt in amidst the vulnerable task-scape for their living. By inhabiting precarious market environments and landscapes, Agariyas challenge their own vulnerability and, through their labor, facilitate deserts’ transitions from barren to fertile landscapes, thereby exemplifying the future of labour resilience in the Anthropocene.

Industry, class, and the ecological crisis: Noxious deindustrialisation and the international division of labour and noxiousness

Lorenzo Feltrin – University of Birmingham

‘Noxious deindustrialisation’ refers to employment deindustrialisation in areas where significantly noxious industries are still operating. According to ILO estimates, this paradox is planetary, as the global share of manufacturing employment slowly declined from 15.7% in 1991 to 13.6% in 2021, to the benefit of employment shares in construction and services. Part of this decline stems from productivity gains in manufacturing occurring more rapidly relative to other sectors, while another factor is the outsourcing of previously in-house jobs from manufacturing to service sector firms (not a mere accounting artifice, as subcontracted jobs are on average more precarious and less paid than in-house ones). Meanwhile, the ecological crisis engendered by industrialised capitalist production – including the deployment of factory-produced machinery and inputs in non-manufacturing sectors and final consumption – keeps deepening.

On a local level, three widespread employment trends can be outlined where noxious deindustrialisation occurs. First, continuing automation reduces the share of jobs in large-scale industry (relative to output and total employment). Second, of the remaining jobs, the most skilled ones are kept in-house, but tend to require formalised qualifications, which provides an incentive for long-range recruitment. Third, the ‘least’ skilled jobs are outsourced to a partially floating workforce of contractors and agency workers. The combined effect is a relative ‘deterritorialisation’ of the workforce of large-scale industry.

On the other hand, fenceline communities near noxious industries are usually disproportionately composed of the most disadvantaged – and often racialised – ranks of the working class (in a broad sense, which includes the unemployed, and reproductive, informal, and unwaged workers in all sectors), because higher-income households can more easily relocate to healthier areas. The employment trends just mentioned mean that such communities remain exposed to significant levels of cumulative industrial noxiousness (despite improvements due to green techno-fixes), but reap meagre benefits in terms of industrial jobs. This increases the chances of intra-working-class tensions between those employed in polluting industries but living far from them and those living nearby but working in other sectors.

While broadly similar trends along these lines can be identified in different parts of the world, each local experience of noxious deindustrialisation varies depending on contextual factors. A key element here is the mode of insertion of the affected area in the ‘international division of labour and noxiousness’, the global socioecological hierarchy constituted by interconnected differentials in technological capabilities, wage levels, and environmental degradation. Colonisation in the so-called Global South was a condition for the industrialisation of the North, which still dominates the technological frontier. This allows Global North countries to constantly re-create export sectors combining an average rate of profit with relatively high wages. Global South countries, instead, must compete through the abundance of their rent-bearing natural resources (cheap nature) or the misery of their wages (cheap labour), both compensatory mechanisms to push laggard capitals closer to (or even beyond) the average profit rate.

This means that noxious deindustrialisation in the Global North can more easily be mitigated through the deployment of cutting-edge industrial technologies and the expansion of relatively decent or even good-quality employment in services. For example, noxious deindustrialisation in Grangemouth (Scotland) was somewhat mitigated via advanced techno-fixes while in Porto Marghera (Italy) the eventual closure of the most polluting factories did not cause an employment catastrophe due to the economic dynamism of the Veneto region. However, even in the Global North, there are many ‘left-behind places’ – such as Taranto (Italy) or Lusatia (Germany) – characterised by laggard, highly polluting industrial processes and depressed labour markets.

Instead, in Global South extractivist contexts – for example the industrial area of Quintero-Puchuncaví (Chile) – noxious deindustrialisation is marked by the economy’s reliance on rent-bearing primary product exports. Here, industries stemming from downstream ‘forward linkages’ to mining often operate with laggard technologies and therefore fall below the best environmental standards. However, their simple closure results in a deepening of extractivism itself while most employment outside large-scale mining and industry is significantly worse in such areas than in the Global North.

The shift to renewables and further digitalisation – the emblem of the green-capitalist quest to reach ‘net zero’ greenhouse-gas emissions by 2050 – is projected to inflate demand for ‘critical minerals’. However, such energy transitions are unlikely to deliver if they remain confined to the realm of technological fixes, without also changing the social relations shaping trajectories of innovation. In this sense, it is also necessary to make political space for a more balanced international division of labour and noxiousness. This is not about ensuring a ‘fair share’ of wages and pollution to all, it is rather a step towards reducing the global intra-working-class stratification that stands in the way of the decommodification of production and nature needed to address the ecological crisis. In the absence of transformations in this direction, the energy transition will merely intensify extractivism and perpetuate – in new forms – the global socioecological hierarchy.

This contribution received funding by the Leverhulme Trust (ECF-2020-004).

Ecology of labour: an ethnographic approach to Portuguese fisheries

Joana Sá Couto – Instituto de Ciências Sociais, Universidade de Lisboa

As a PhD candidate in the Doctoral Program on Climate Change and Sustainable Development Policies, I am interested in better understanding the human-nature relationship within two Portuguese fishing contexts. During my master’s degree, I considered that it is important to share local knowledge and the significant impacts of the capitalist neoliberal economic systems on the daily lives of local communities. During my PhD, personal and academic interests led me to explore such issues.

One of the oldest forms of relationships with nature is fishing. This activity is not just an extractive activity. Fishers describe reasons why they love this way of life: the freedom, being their own bosses, going out to sea as a child with the family and feeling a sense of attachment to the seascape. It is also, admittedly, a repetitive and embodied form of labour. Mind and body emerge as one in an environment that can potentially be deadly. Understanding these and the impact that capitalism has on the daily lives of fishers is essential for ensuring the sustainability of marine resources.

There is an important know-how in fishing, through socialization, daily life, and the repetition of tasks and activities. The increase of knowledge is inherent in the act of existing in the environment, whether you are fishing in a small rowing boat or a large trawler. However, there are differences in the way knowledge is transmitted, with impacts on the social fabric of the community. In Setúbal, younger fishers stay clear of learning some techniques of mending and re-using materials, fearing they will have to work more hours without pay, or because they simply may not have interest in learning them at all. Also, with nylon nets it is simpler and cheaper to buy new net panels than mending them, contrary to cotton ones. As Setúbal, a retired fisherman observes: “Now with nets of this material and cheaper, they prefer not to learn anything and throw it away. I really liked learning though. I already told you that my biggest regret was not going to school.”

With migrant workers in Sesimbra, language is the first barrier. Basic English is used to teach something or through which to order necessary tasks. Here, observation and body movements are crucial, and even more important than verbal language. Migrant workers watch closely and mimic body movements as a way to get around language barriers. Few are the conversations they have with the rest of the crew, only if there are others who share their native language. Their clothing is similar, their movements the same as other workers, but they are more downcast and appear quite excluded from activities such as going to the cafe or religious activities related to the patron saints of fishermen, as alluded to by one African migrant worker: “I don’t have a family, I don’t have friends or know many places here.”

The issue brought forth in this ethnographic work within two fishing contexts is a multi-layered issue of environmental justice. On the one hand, the way fisheries are managed in Portugal and the entire ideology of ‘blue growth’ is placing smaller-scale fisheries at a disadvantage when compared to industrialized fisheries or even aquaculture. On the other hand, this market and resultant political pressures has harmful effects on the social fabric: namely, seeking profit and increasing stratification, especially now with migrant workers being seen as cheap labour and not as part of the community. Studies on these dynamics are crucial for us to understand how the organizational form of capitalist systems is having effects not only on the planet but on the communities themselves, on their way of relating to nature and to one another. This is becoming increasingly problematic when you see that the devaluation of the class of workers that are the fishers leads to fewer people interested in joining the profession, resulting in the exploitation of racialized migrants who need employment. This is a working class that is becoming increasingly stratified and getting further away from the concept of community; thus, sustainability cannot exist in this context.

When we discuss ecologies of labour in the case of fisheries, we can see how climate change is more than an ecological issue, it is also a social and economic issue, indeed, a class struggle. The sea is a place of work, and it can remain a welcoming one through appropriate conservation efforts.

Feminist Ecologies: Navigating Critical Intersections

Professor Anastasia Christou – Middlesex University

Current ecological crises call for academic activism to understand planetary destruction in theorising extraction and injustice, particularly through an interdisciplinary feminist-ecology lens that embraces decolonial/anticolonial feminisms and action. Spatial and temporal contexts for recognising and analysing extractive systems of ecological destruction, when situated in spheres of indigeneity as emancipatory ecologies, can subvert intersectional oppression (based on gender, race, ethnicity, class, sexuality, age, ability), and other forms of injustice.

Feminist political ecology and indigenous knowledge are important for grounding diverse theorisations of social relations of power associated with natures, cultures and economies. Long faced with histories of dispossession and displacement, indigenous knowledge systems are committed to intersectional epistemologies, methods and values, where dominant, masculinist conceptions and practices of authority are recognised and challenged. Aligned to this, an emphasis should be given to practice that empowers and promotes justice-driven social and ecological transformation for women and other marginalised groups. Peace, peasant, indigenous and women of colour-led movements have never been limited to protecting their own rights and interests. Their struggles and demands are also about the human rights, environmental and civil commons issues that impact us all.

Ecofeminist-driven analyses unravel entanglements and genealogies of justice, feminist, queer, decolonial post-humanist ecologies, thus opening up radical possibilities to engage with other worldviews and ways of knowing. In this direction, by bringing in diverse networks of thought and practices into conversation with wider racialised and gendered dynamics of resource access and dispossession, we can address diverse materialities, embodiments and aesthetics through a feminist and decolonial ethics of care, transversal politics and transnational impacts. By extension, such approaches aim to showcase multidimensional critical questions and concerns that each of these threads raises.

In combining the interconnected storied negotiations and articulations of imagined futurities of peace and post-pandemic contexts, the relational threads of patriarchy and power, as well as labour ecologies, can be conceptualised through radical affective aesthetics. The dynamics, possibilities, plans and publics involved articulate how relational subjectivities address the temporal and spatial grammars of contemporary social movements such ecological and labour movements. By drawing on a multi-faceted conceptualisations of eco/feminisms, intersectionality and the politics of activist sustainability, we can holistically re-envision how equitable and just societies require the re-working of interconnections and inter-relationalities for collective transformations. The three strands of thought can ground the exploration of such phenomena in an effort to deconstruct pathways of futurities in social movements, and help understand the implications of caring ethics, radical aesthetics and relational subjectivities.

Care ethics can serve as a basis to clarify the nebulous interconnections of materialisms, affectivities and ethical feminisms when it comes to disentangling exclusions from the individual experience to a social platform of wider collective responsibility, which can in turn assist in tackling some of the traumatic and destructive effects as we create more robust commons. Linked to this, contemporary anti-colonial, anti-capitalist ecofeminist strands have everything to do with contemporary lived experience. The case for an imperative of ecofeminism rests on the proliferation of ongoing exclusions, racialisations and the gendered violence of extractive practices.

What has changed in the past few years is the maturing of a near-decade long reawakening of progressive labour and activist cultures and demands, in social movements like Black Lives Matter, Idle No More, #SayHerName, and #NeverAgain. Today’s social movements have put the interests and demands of the most vulnerable at the forefront and begun to mainstream demands for systemic and structural changes. We can see this in part in the growing public need for knowledge about workable alternatives to capitalism, as well as in the anti-capitalist uprisings in more than a dozen countries from Europe to the Middle East, Hong Kong to Chile.

At the same time, despite resistance, sexism and racism are blunt instruments used to maintain the divisions and hierarchies required to keep alive capital’s exploitation of labour and our natural environment. Humanity also faces an existential threat in the form of mounting impacts on land, animal and human lives, livelihoods, increasing environmental displacement through rapidly unfolding climate crises, generated by the same capitalist hierarchy. Overcoming climate chaos requires overcoming the necropolitics of capitalism; and overcoming the necropolitics of capitalism means uniting the exploited classes to realise and universalise alternative formations of political economies that support dignified ways of living. We continue to struggle to create, defend, and elaborate new- and to improve existing- potential solutions to the socio-economic and ecological problems exacerbated by capitalism, and we need to prioritise forging intersectional unity in order to address and solve them.

Right to Employment & Ecology of Labour: Examining India’s Employment Guarantee Scheme

Anjana Rajagopala (Senior Research Fellow, International Institute of Migration and Development, Trivandrum, India) & Rakesh Ranjan Kumar (Assistant Professor, JK Lakshmipat University, Jaipur, India)

India’s growth is characterised by joblessness and job losses (Kannan and Raveendran, 2019). Whilst India is a labour-surplus country, rural India remains agrarian, necessitating interventions for reducing socio-economic vulnerability. The landmark Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Scheme (MGNREGS, 2006) which was passed as an Act, seeks to provide at least 100 days of guaranteed manual wage employment. MGNREGS has served as a buffer to combat unemployment, reverse migration, rural re-agrarianisation, and continues as a means of sustenance for millions. It also integrated ecological development in its framework by creating green jobs in restoring rural ecosystems.

Studies in Kaimur district of Bihar (ILO, 2010) and Shivpuri district in Madhya Pradesh (Narwaria, 2013) reported ‘Green’ and ‘Decent’ works created by MGNREGS through ensuring labour rights and entitlements, guaranteed employment with social protection under ecological works of MGNREGS, improving irrigation and drought protection. A study by the Tata Institute of Social Sciences (TISS) in Jalandhar on cross-convergence of MGNREGS with the ‘Seechewal-Model’ related to wastewater management for irrigation that used purified sewage water, found positive instances of convergence of schemes leading to mutually beneficial outcomes in employment and ecological wellbeing. A similar report on Rajasthan in 2021-22 revealed that convergence of MGNREGS with Jal Shakti Abhiyan (JSA) helped in urging communities to conserve water, while focusing on natural resource management (NRM) works under differing agro-climatic zones. The study found good quality NRM works in 42% sampled villages, with 79% local bodies reporting significant benefits.

NRM works under MGNREGS include water conservation, irrigation, conservation of traditional water bodies, watershed management, afforestation and land development. Between 2014-15 and 2022-23, the largest increase in expenditure was noted in irrigation (81% per annum), followed by watershed management (37% per annum). Afforestation and water conservation saw an annual increase of 28% and 24% respectively, while land development and traditional water bodies saw the least increase in expenditure (17% and 10% annually, respectively). While considerable focus within NRM was laid on irrigation and watershed management, all works under NRM steadily received increasing expenditures over the period. Total expenditure on NRM activities under MGNREGS during this period grew at 25% annually, indicating the growing focus on maintenance of ecology while guaranteeing rural employment.

MGNREGS also focuses on water stressed areas through Mission Water Conservation (MWC) blocks. The share of MWC blocks that received more than 65% of expenditure on NRM showed a fluctuating trend between 2014-15 and 2022-23, with considerable interstate variations. Kerala remained the only state with all MWC blocks receiving at least 65% expenditure on NRM, followed by Andhra Pradesh. However, the states of Himachal Pradesh, Uttarakhand (in the Himalayan mountainous regions), and Assam and Bihar (in flood-prone eastern India) received the poorest share of NRM expenditure in MWC blocks. As Bihar is a migrant-sending state, creating NRM works within MGNREGS in Bihar could help reduce distress-related migration as well as climate vulnerabilities.

Under MGNREGS’s NRM works, soil and water conservation related works received the major thrust, with 77% annual increase in expenditure, followed by plantation works (8% annual increase in expenditure). However, Drainage and other Related Works as well as Land Related Works for Livelihood support received decreasing share of expenditure over the years (12% annual decline in expenditures). The share of NRM works to total works under MGNREGS has more or less remained stable at around 40%. Corresponding share of NRM expenditure to total expenditure under MGNREGS has been gradually increasing, from 58% in 2014-15 to 64% in 2022-23 and 74% in 2023-24. Overall, the importance of NRM works and expenditure has been increasing over time within MGNREGS, highlighting its emphasis on ecological development along with labour.

States like Assam, Bihar, Madhya Pradesh, Maharashtra and Tripura showed a decline in NRM works between 2014-15 and 2022-23, despite positive trends in expenditure on NRM. On the other hand, states like Karnataka, Odisha, Chhattisgarh, Manipur and Meghalaya witnessed significant spikes in NRM related works within MGNREGS along with increase in NRM related expenditure. Overall, while NRM expenditure showed an increasing trend (of 1.2% per annum over the period of 2014-15 to 2022-23), NRM works at the same time showed annual decline of 1.7%. This has been commensurate with an almost stagnant rate of employment under MGNREGS as a whole. In fact, a declining trend in job-cards was witnessed after 2021-22.

Case studies in India highlight positive impacts of NRM works under MGNREGS on environmental and labour development. Data show that NRM expenditure within MGNREGS rose between 2014-15 and 2022-23. However, inter-state variations reveal cases where NRM expenditure increased, but share of NRM works to total works did not increase commensurately, indicating possible inefficiencies. It therefore becomes essential to document good practices and ensure that MGNREGS’s NRM expenditures translate into increased job opportunities along with ecological development.

Indigeneity, Nationalism and Ecological Justice: Shifting Scales of Statelessness

Ram Kumar Thakur

The ‘being’ and ‘becoming’ of nation-states is often riddled with populist notions of ‘rightful’ belongingness and a sense of historical hurt and pride. The self-determination of ‘indigenous communities’ opens up the scope for creative conversation and conflict with the dominant paradigm of the nation-state, be it through the ideas of federalism or legal safeguards of communitarian autonomy. Furthermore ,ecology becomes a very important arc around which the politics of belongingness operates. The different constituencies of nation state along with ‘Indigenous communities’ mark their association with territoriality, flora, fauna through authoritative assertions of participative labor in the making of history. Such invocations simultaneously operate within and outside the fold of the nation-state. The pride and prejudice surrounding ‘sons of soil’ discourses, specificity of development of nationalist identity, along with the new found international political vocabularies of indigeneity complicate the supposed consensus of governmentality categories. The plurality of discourses surrounding social formation of identity and its corresponding officialization as such always carry remnants of fissures in actually existing political discourses, be they liberal democratic or authoritarian.

The debates on history of colonialism, cartographies of administration, indentured labor and migration, conservation of natural habitat versus encroachments, etc., have a direct bearing on the contested history of the present. Contemporary political discourse builds up on authoritative accounts of belongingness by weaponising ecological discourse on conservation, threats to land, culture, resources, employment, etc., against the perceived ‘other’ of migrants along multivalent lines. Both the nationalist and sub-nationalist politics of indigeneity instrumentally invoke the ‘quintessential other’ to firefight legitimation crises of governance and democracy emerging from capitalist development. The racialized linguistic, religious and working-class minorities generally suffer both legalized subjection and exclusion from the dominant communities, as well as precarious positions within capitalist labor relations. The citizen-population axis of any democratic nation-state functions within the idioms of bundle of individual/group differentiated rights and duties. These basic conceptions of ‘right to have rights’ undergo crisis when populist majoritarianism takes over genuine concerns of decentralization and autonomy along exclusionary lines.

Further, on many occasions the concern over preservation of land, resources, culture, etc., could actively metamorphose into patriarchal community control over sexual and martial relations, and property regimes. Ecological disasters such as earth-quakes, floods, etc., along with persecution of political dissenters could also open up the scope for mass violence, large-scale migration and refugee crises potentially leading to statelessness. The territorialization of complex history of migration into a homogenous nationalist identity, by marking out ‘true’ heirs of nationalism, opens up the scope for illiberal politics and non-reflexive communitarianism. To understand the instrumental usage of ecological discourse of injustice one has to dive deep into the complexity and historicity of indigenous politics surrounding nomenclatures. The essentialized discourses around governmentality, and the corresponding negotiation by communitarian groups along different axes of self-determination, language, law, religion, along with political vocabularies of insider/outsider, legal/illegal, original/non-original inhabitants, inhibit the possibility of easily agreed upon perceptions of shared belongingness. The South-Asian sub-continent has had a history of both coercive and voluntary migration mediated through colonialism and post-colonial governmentality exercises.

The recent changes in the Citizenship Amendment Act, 2019 in India provides avenues of citizenship for non-Muslim persecuted minorities living in neighbouring countries. The registered changes have challenged the secular basis of citizenship by marking political minorities and specific religious minorities as deserving, through selective state patronage and exclusion. Another governmentality exercise portrayed along secular lines is the effort to establish documentary citizenship in Assam through National Register of Citizens (NRC), which has opened up new fault lines of ‘statelessness’ for linguistic and religious minorities of more than 19 lakh people. The discourse of illegal migration in Assam has been historically framed through the lens of threats to ‘indigenous people’ and ‘their ecology’ by the supposed ‘invading land hungry immigrants’. History of migration appears in the popular prejudiced discourse as a conscious political strategy of control, hegemony and aggression against the culture, ecology and politics of the ‘indigenous people’. Even the courts of law have officialized such populist ideas.

I argue that in such scenarios both the international discourse of Indigenous rights and nationalist tropes of truncated inclusion are pitched through the language of human security and national security respectively. These insecurities on most occasions use the tropes of ecological injustice. The matrix of nationalist and sub-nationalist grievances and instrumental usage of perceived fear and threat create difficult scenarios for the migrants, refugees, etc., to stake claims as equal civic subjects. The asymmetrical discourses on belongingness foreclose the possibility of dignified human and political subjectivity for a large mass of people, risking alienation and violence from the political community, and even opening up the spectre of statelessness through a populist democratic consensus.

Leave a comment